Jelly Bucket [jel-ee buhk-it]-noun

- Archaic slang for a lunch pail, formerly used by coal miners and other laborers residing in Appalachia.

- Bluegrass Writers Studio’s annual graduate-student-produced literary journal.

Preview cover art and selected works in each genre for each journal

Featuring work by Priscilla Adkins, Melanie Crow, Taylor Hodge, Roger Pincus, Dan Sociu, Steve Tompkins, and many more. 198 pages.

Matthew Burns

I Am in Love with Air

On the flier for used textbooks and second-

or third-hand furniture taped to a classroom door,

someone has used their felt-tip pen

to print, in heavy black caps, FUCK IT ALL.

And I love that you can tell

by the way every line either starts

or ends with a dark blot, where the nib rested

just a moment before being pulled

through the clean architecture of its letter,

how this was constructed; like whoever was here,

late for an engineering class, or just leaving early

from a test he knew he failed,

drifted out the door in the cool moment of recognition

that perfectly blends epiphany and dread

into something entirely fresh that—and here’s where

the sadness comes in—is uncannily familiar.

Suddenly there was plenty of time to think this statement through,

and build it as he went.

I can respect the kind of focus and attention to craft

that would probably make this frustrated kid

a pretty solid engineer—not that I know the qualities

that make a solid engineer,

but I imagine good penmanship would be one of them.

A little dispatch—to everyone, to no one,

a bottle tossed into an ocean filled with doubt—

the perfect Dear John, with the whole world

unwittingly cast into the role of John.

So unlike the wild hand who felt the need

to answer this dark epistle

with a single strikethrough and, below that,

I AM IN LOVE WITH AIR

cursived in soft pencil and even flourished

with a long wisp from that last rounded R,

like a kite string or loose hair trailing on an invisible breeze

blowing across the untouched white fields of the page.

And I’d put money on it being the work

of one of the dozen art students

who’s passed by on his way to the café

to doze off a mid-week hangover before a class

he may or may not attend—he hasn’t decided yet

because, Man, he thinks, isn’t it more important

to be out there living, sleep when you’re dead,

carpe diem, and all that?

I am growing older. I am jealous.

I want to love air again and do some for-show-type shit:

carry beat-up paperbacks everywhere with me—

Whitman in one back pocket, Wilde in the other,

letting their words pat me on my scrawny ass.

And it wouldn’t matter which books they were, either,

they’d all say the same as far as I’m concerned:

adore everything, even the stuff you can’t see.

And what better way to trudge through this whole thing

than with a blushing smile and a face turned to the wind?

Her soft hands slapping one cheek then the other

as the scraps of all our screw-ups

blow away like petals down the street

and we say fuck it all

with the perfect calligraphy of a middle finger.

Matthew Burns is pursuing a PhD in creative writing at Binghamton University where he is poetry editor for Harpur Palate. He has been nominated for the AWP Intro Journals Project and won an Academy of American Poets College Prize. His poems have appeared or are forthcoming in Cold Mountain Review, The Georgetown Review, Paddlefish, and Upstreet, among others.

Featuring work by Angel M Baker, Richard Garcia, Chris Offutt, Henry Presente, Charles Rafferty, Tea Topuria, and many more, with cover art by China Marks. 190 pages.

Chris Offutt

Ghosts in the Attic

considered this evidence of my imagination, vast even for a child, and took possession of a large house on an isolated hill in eastern Kentucky, surrounded by the Daniel Boone National Forest. A dirt road led up the hill from the blacktop below.

The front of the house had four windows, two on the first floor and two on the second floor. Decorative shutters made of painted wood flanked the upstairs windows. The front door had a small, covered porch. Above its flat roof was another set of matching shutters. These, however, were shut, as if blocking an unseen window. Throughout my childhood, I believed those shutters concealed a secret entrance.

The house had three bedrooms—one for my parents, one for my sisters, and one for my brother and me. Our bedroom had a large closet, more of a small room actually, and inside was another door that opened to a narrow stairwell leading to the unfinished attic. The closed shutters were on the other side of the closet wall. I became certain that ghosts lived in the attic, entering and departing the house through the closed shutters. The closet provided them access to our room. My brother’s bed was against the far wall, but mine was beside the closet door. Each night I created a barrier of pillows to protect me from the ghosts. I kept rocks in my bed to defend myself in case they attacked. I slept at the far edge of the bed with my back turned to the door, my arms and legs tucked close. In this way I went to sleep in fear every night.

I did not have the kind of family that talked about personal concerns, and no one knew about any of this, not even my brother. Within a few years, prior to puberty, I developed the habit of sleepwalking, leaving the room to awaken elsewhere, occasionally outside. I often awoke from nightmares, sweating and scared, unable to recall what had transpired, knowing only that the ghosts had entered my room from the closet. I lay in bed rigid and tense, listening intently for evidence that a ghost still waited to ambush me as soon as I closed my eyes.

When I was twelve, my father quit his job outside of the house and began working from home. To accommodate this, he took my sisters’ small bedroom and they moved into my bedroom. My brother and I were relocated upstairs—the attic newly refinished but still containing evil ghosts. The space was long and narrow with a ceiling that slanted to low walls, which held two doors made of planks that opened to the eaves. I understood that the ghosts lived in there now, behind these flimsy doors, pushed into new quarters like my siblings and me.

To access my new bedroom, I was required to enter the dread closet through the creaky door and climb the dim steps to the completely dark room above. Worst of all, the only light switch was on the wall at the top of the steps. This presented a dilemma: did I sneak up the steps so as not to alert them, or make a mad dash and hope that my speed was greater than theirs. Each option had its own risks and gains. Both were fraught with terror. The sneaky way gave the ghosts time to position themselves. Racing up the steps offered me the advantage of surprise, but made me more vulnerable if the ghosts heard me. I decided on running upstairs, mainly to get the task over with quickly. I didn’t think I had enough courage for the slow approach.

I doubt my parents knew the degree of fear with which I approached my bedroom. They certainly never asked, and as oldest child, I didn’t want anyone to know how afraid I was. My brother and I never had a flashlight, nor was there ever any talk of one. Flashlights were reserved exclusively for those times when the electricity went off.

My brother refused to enter the room alone. Each night, he waited in the dark closet, while I inhaled deeply, ran swiftly up the steps, hit the light switch with my open palm, and jerked my head in all directions to check for ghosts. They were always gone. My speed and agility had beaten them again. Occasionally I saw the flicker of their disappearance as they returned to their haven in the eaves. For the next five years, I ended each day in this fashion until leaving home at seventeen.

Since then I have believed that every place I lived in was haunted. The previous occupants had probably left due to the presence of ghosts, and since most were rentals, I figured that’s why no one wanted to own the house in the first place. I’d spend the first week in a new place lying awake at night, learning each sound–the refrigerator’s motor, air in the water pipes, the rattle of a window casing, the whistle of wind. Over the years, I developed a variety of methods to keep the ghosts at bay. The most crucial was closing the closet door before going to bed. If the bedroom opened to a bathroom, that door needed to be shut as well, after checking behind the shower curtain. Bureau drawers were closed tightly, curtains were drawn, and the bedroom door itself double-checked that it was latched. Any rug was smoothed out. Though I have lived in more than forty different apartments and houses, I never discovered any evidence of ghosts, which was proof that my precautions were effective. However, I have always felt slightly disappointed. Seeing a genuine ghost would grant credence to the intense fear of my childhood room.

I spent more time outside our house than in, wandering the woods that surrounded the house. A couple of footpaths went along the ridges to a distant neighbor’s house, and another ran off the hill to the creek. Each morning I followed a path through the woods to school, a shortcut from one part of the dirt road to the other. I particularly enjoyed the woods at night, the mournful call of whippoorwill and owl, cicadas droning in the distance, the wind in the high boughs. The dark woods offered a solace that I relied upon. Later, after leaving home, I was surprised to learn that most people are afraid of the woods at night, that the menacing woods are a staple of fairy tales and pop culture. My experience was the opposite. Many times I left the house at night wishing I could remain in the woods forever.

My parents still live in the house I grew up in. They converted my old room in the traditional way of an abandoned nest – first to a sewing room, then to a study when my mother took classes, and lastly to a storage for junk. My siblings and I seldom go home. When we do visit, we get a hotel room in town. I recently spoke to my sister on the phone, and casually asked if she was ever afraid of the attic. She immediately said she was afraid of the whole house. I couldn’t answer because I had no idea what to say. I still don’t. My brother once told me that when he climbed the steps to our old room as an adult, something cold always passed through his body. He believed that it was the ghost of his fear.

On my last trip home, I stood in the dark closet at the bottom of the dark steps. The bedroom above was utterly black. I listened intently for any sound from the ghosts. I inhaled deeply. I placed my hands on the door jamb and used it to catapult myself up the steps, knowing just where to place my feet to avoid each creak, and at the top of the stairs my open palm hit the light switch and I jerked my head both ways and knew I had defeated the ghosts. I made it. I was safe. I was forty-five years old and had successfully entered my room again.

The contents of my former bedroom were organized into tall stacks that included Christmas decorations from the fifties, clothes from the sixties, and high school yearbooks from the seventies. There were broken toys and games with missing pieces, boxes of junk, dishes, magazines, and old luggage. My parents grew up during the Depression and their childhood fear was deprivation, not ghosts. My father saved soap slivers to prevent waste, and my mother has thrown away very little since moving to this house. She once informed me that she didn’t want to inconvenience the garbage men.

The room was ten times smaller than I remembered, as if the world of my childhood had shrunk. I wandered among the maze of piled objects, touching this and that. I handled things that were significant enough to save, but that I now barely recalled. It was like being at a yard sale, going through the remains of another person’s life. I had become my own ghost.

I found a charcoal sketch of my brother that someone made when we were kids. I remembered when it was drawn. At the time I didn’t believe it looked like my brother, but I knew that in the future everyone would think so. I held the picture in both hands, stunned that a child would have thought that way, more surprised that the child was me. I stared at the picture for a long time. It did in fact resemble my brother. Oddly, the drawing looks more like him now than it did then.

I crossed the room and turned off the light and stood in the dark. I didn’t feel afraid. It was just the storage room of an old house in disrepair. My memory was all that haunted the space. The hinges creaked on the door at the foot of the steps. I recognized the sound as one I’d many times opening the door slowly so the ghosts wouldn’t hear.

I thought of a young boy running up the stairs, his heart pounding, his feet finding each dark step, his hand hitting the light switch. He was lonely and imaginative. His parents were gone. I moved quickly and hid in the eaves so he would not mistake me for a ghost. At the top of the steps he jerked his head in all directions as the light came on. The room was safe. The light dispelled the ghosts. He was breathing hard.

He glanced at the area where I was hiding, the small door set in the low wall of the eaves. I held my breath. The boy stared at the crack between the door and the frame. I watched him swallow, his throat pulsing from fear. He walked to his bed, turned on the reading lamp, and returned to the top of the steps. He was deliberately not looking toward the eaves where I hid.

He turned off the overhead light and ran to his bed and jumped in. I knew that he would sleep with his arms and legs tucked beneath the thin sheet, no part of his body hanging off the edge of the mattress as an enticement to the ghosts. He would sleep that way the rest of his life.

When he at last did drift into sleep, I quietly left the eaves, opening the low door carefully, so as not to disturb him. I walked to the top of the steps. The room was very dark, but I could see his darker shape humped in the middle of the bed. I eased down the steps, knowing each tread intimately, able to find the precise spot that would not squeak.

At the bottom of the steps I faced a dilemma. The closet door always creaked when it opened, the hinges rasping, the swollen wood sticking in the jamb. It would be impossible to leave without making noise and scaring the boy. I stood for a long time in the dark closet, debating the options. I could sneak back up the steps or I could simply open the door. Either way, the boy would wake up terrified from a bad dream. At the same time, I couldn’t remain trapped in the darkness myself. I had to depart without disturbing the child above. I stepped close to the wall, opened the shutters easily, and left the house for the safety of the woods at night.

Chris Offutt grew up in Haldeman, Kentucky. He is the author of Kentucky Straight, Out of the Woods, The Same River Twice, No Heroes, and The Good Brother. He has written screenplays for True Blood, Weeds, and Treme, and TV pilots for Fox, Lions Gate and CBS.

Featuring work by Eileen Casey, Stuart Dybek, Austin Hummell, Sonja Livingston, Vera Pavlova, Frank X Walker, and many more, with cover art by Joe Decamillis. 198 pages.

Stuart Dybek

Among Nymphs

After midnight, when the only café insists on closing, they follow the cork-screw street that leads like every other street in the village to the fountain. If they can find the fountain, then, even in this darkness they can find their hotel, which overlooks the fountain, although their room does not. Nonetheless, with the window open they can hear the fountain keeping time through the night, with its plashing, or rather, making time seem inconsequential, at least for as long as their money holds out. Each night they’ve been falling asleep to the echoes of water echoing water. By morning when they wake, the burble of water is no longer audible above the hubbub of the foreign voices rising from a village going about its business.

Of course it is really their own voices that are the foreign ones here where they have no business to be, where they’ve come by accident—another in a succession of accidents between them, but finally an accident in which no one has been hurt. Even their laughter as they tipsily make their way back, almost having to feel along the rough, stone walls of houses in the total darkness of the narrow street, sounds foreign and out of place.

“Shhh,” they shush each other and then laugh. He can hear her laughter rising to the musical pitch of water, echoing off before them down the street.

“Shhh, we have to keep it down,” he says, and they stop and kiss hard as if to seal each other’s lips, and kissing like that they dizzily lose their balance and have to steady themselves against a wall. Her back against the wall, he draws her hips toward him, and their bodies grind together.

“You’re not following your own advice,” she says, her voice sounding winded beside his ear.

“What advice?”

“To keep it down,” she whispers, and then bursts into a drunken fit of giggling.

Above the narrow street, the moon is a blank in the sky. When the café sign blinks out behind them, he tells her they’ve just reentered the Dark Ages. In the entire village, only the single streetlight beside the fountain still burns.

Gawking above the ancient square, the streetlight seems a mistake. Given its glare, it is probably a lucky thing that their room doesn’t face the fountain. In the harsh yellow glare, the fountain appears fissured with cracks, crumbling, eroded by its own gush of water. During the day, they’ve noticed workmen patching the cracks and skimming leaves and debris off the surface of the fountain pool with long handled nets that look as if they’d be good for catching butterflies. But at night new leaks spout and puddle the cobblestones so that it looks as if a rainstorm has just swept the square. Tiny tributaries, each with its own current, trace the decline of the street that slopes down towards “the thousand steps.” Step by step, water trickles towards the village on the hillside below, a village that doesn’t have a fountain. Instead of a fountain, that village is famous for the corpse of its patron saint, which, over centuries, has refused to decay. They decided not to stay in the village with the saint.

Tonight, with no one else awake, she slips her sandals off, raises her skirt, and wades into the pool. Spray plasters her blouse against the contours of her body and she opens the buttons until her wet breasts gleam. He watches her standing, her throat arched back, her eyes staring up at the night, and he’s glad they’ve come here away from everyone to whom they’ve become strangers. Maybe they needed to be foreign, he thinks, to find a place they had no place in beyond being strangers. Even now he feels like a stranger to himself, still not sure why he’s needed this woman that he’s given up so much to have.

He watches her and wonders how, come morning, when the village wakes to the greetings of roosters and doves, it would look to find her still standing half bare, waist deep in the dark swirl, her hair drenched with the shower of spray, a strange woman among the familiar nymphs pouring out their bottomless urns, her eyes too much like theirs, intent upon some nameless mystery, daylight white on their graceful limbs, all of them in the fountain standing poised even as the fissured walls give out and a torrent of water floods along the cobblestone street, cascading down the thousand steps like a waterfall, and the men from the town below rush out carrying their incorruptible saint and praying in a foreign language they themselves don’t understand—that no one, perhaps not even God understands—as they ascend the steps, fighting their way upstream with the mindless ardor of spawning salmon.

Stuart Dybek is the author of three books of fiction: I Sailed with Magellan, The Coast of Chicago, and Childhood and Other Neighborhoods. Both I Sailed with Magellan and The Coast of Chicago were New York Times Notable Books, and The Coast of Chicago was a One Book One Chicago selection. Dybek has also published two collections of poetry: Streets in Their Own Ink and Brass Knuckles. His fiction, poetry, and nonfiction have appeared in The New Yorker, Harper’s, The Atlantic, Poetry, Tin House, and many other magazines, and have been widely anthologized, including work in both Best American Fiction and Best American Poetry. Among Dybek’s numerous awards are a MacArthur Prize, the Rea Award “for significant contribution to the short story form,” PEN/Malamud Prize “for distinguished achievement in the short story,” a Lannan Award, a Whiting Writers Award, an Award from the Academy of Arts and Letters, several O. Henry Prizes, the Nelson Algren Prize, and fellowships from the NEA and the Guggenheim Foundation. He is a Distinguished Writer in Residence at Northwestern University and a member of the permanent faculty for Western Michigan University’s Prague Summer Program.

Sonja Livingston

Pistacia vera (Pistachio)

The Aegean Sea. I promise you will never see such blue. So why do I stare at the earth? The surface of this Greek Island is cracked, grows wild silver trees. Ugly as hunter’s hands, the branches grab me. Won’t let go. Like those boys who held me as a girl, making me watch as the rabbit they’d caught was skinned. “Just look and we’ll let you go” they said, and the guts slid out smooth and red as kidney beans. I cried and hated them. Hate them still. But hate is a sad foolish thing because those boys never lost their hold, not really, and it’s this hold you have on me now, wicked branches, as I turn from the sea and stare into your thorns, caught up by bones that breathe life. I forsake the clean sapphire of the Aegean, pass over oleander and lemon, just to stand by your side; pressing into barbed wire and staring into the past. Could I have closed my eyes? Did I wonder about the insides of rabbits? No, it was only those boys. Their grubby hands. And your branches. Old as time, still bearing fruit.

Sonja Livingston’s essays have been honored with a NYS Fellowship in Literature, Iowa Review Award, Pushcart Prize nominations, and grants from Vermont Studio Center and The Deming Fund. Her work appears in many literary journals, and is anthologized in several textbooks. Her first book, Ghostbread, won the AWP Award for Nonfiction. Sonja is an Assistant Professor at the University of Memphis where she gawks at Elvis fans and dreams of snow.

Featuring work by Adam Day, Lyn Hejinian, Anothai Kaewkaen, Bronislaw Maj, Joel Peckham, Glen Retief, and many more, with cover art by Brian Dettmer. 190 pages.

Ocean Vuong

A Kind of Kindness

The night he chooses her

instead, you find yourself

on the sagging porch, watching

a lone moth bash herself against

the lamp. That relentless ticking—

fury thrown again and again

into light—until dusty wings unravel.

And because

you’ve always been reckless

with tenderness, you gather

the small panic in your hands,

part your lips and try

to stitch a song

into gauze. But what good

is music if not to trouble

the air? What good—if not

the cold rooms, the bed

made emptier with moonlight,

where you’ll crush yourself,

skillfully, into no one’s arms.

Ocean Vuong is the author of two chapbooks: No (YesYes Books, 2013) and Burnings (Sibling Rivalry Press, 2010), which was an American Library Association’s Over The Rainbow selection. A recipient of a 2013 Pushcart Prize, he is a recipient of fellowships from Kundiman, Poets House, and the Saltonstall Foundation For the Arts, as well as an Academy of American Poets Prize and the Connecticut Poetry Society’s Al Savard Award. Poems appear in Poetry, The Nation, Quarterly West, Passages North, Guernica, The Normal School, Beloit Poetry Journal, Denver Quarterly, Best of the Net 2012 and the American Poetry Review, which awarded him the 2012 Stanley Kunitz Prize for Younger Poets. Work has also been translated into Hindi, Korean, Vietnamese, and Russian.

Born in Sai Gon, Vietnam, he currently resides in New York City where he reads chapbook submissions as the managing editor of Thrush Press. He thinks you’re perfect.

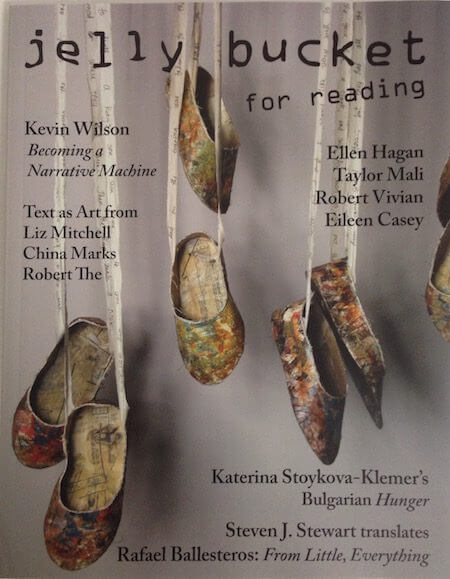

Featuring work by Kevin Wilson, Ellen Hagan, Taylor Mali, Robert Vivian, Katerina Stoykova-Klemer, China Marks, Eileen Casey, Robert The, Steven J. Stewart and Raphael Ballesteros, with cover art by Liz Mitchell. 96 pages. New 8.5″ x 11″ format.

Taylor Mali

The Sound of Hammers Falling

– For Victoria Soto

One of my students said it sounded like hammers falling.

Isn’t that simply beautiful? The sound of hammers falling?

That’s what I call poetry: To think of hammers falling.

To hear it in your head, that sound of hammers falling,

the metal pop and clank that makes the sound of hammers falling.

The tumbling to the ground that is the very sound of hammers falling.

I hid some students in the bathroom when I heard the hammers falling.

Locked others in the closet to avoid the hammers falling.

Shut the rest behind cupboard doors because it was not hammers falling.

Welcome to my empty classroom. Can’t you see

my students are not here. There is only me

and the rainlike patter of footsteps in the hall.

My name is Vickie Soto. Let the hammers fall.

Taylor Mali is one of the most well-known poets to have emerged from the poetry slam movement and one of the original poets to appear on the HBO series Def Poetry Jam. A four-time National Poetry Slam champion, he is the author of two collections of poetry and a book of essays, What Teachers Make: In Praise of the Greatest Job in the World. In April of 2012, Mali completed a 12-year project of convincing 1,000 people to become teachers and marked the occasion by donating 12 inches of his hair to the American Cancer Society.

This issue features poets Tyler Dettloff and Kristina Erny and artwork by Valerie Savarie and others. 160 pages.

Christine Holmstrom

Hunted

“You remember the incident last November, the Thompson escape?” The chief deputy warden inclined his head in my direction, recounting the event as if my memory needed a nudge. “And the armed accomplice, David Hunt . . . ”

Biting my lip, I stifled the urge to scream. Like I was going to forget being shoved into the back of a rusting prison transport van, a shotgun pointed at me, sure I’d be dead in minutes.

In November 1980, I’d been on my way out San Quentin’s count gate after an eight-hour graveyard shift when the watch sergeant hollered, “Hey, Holmstrom, easy money. Got a medical run for you.”

I was happy to grab overtime. The next month, I’d be on a plane to Europe to meet up with my boyfriend. Sleep be damned; I could stay awake for a couple more hours to haul some low-custody—”good guy”—prisoner off to a doctor’s office in town. I was unarmed. It was me and a medic named Ruff. Two hours and I’d be in my car, heading for home. What I hadn’t planned on was David Hunt, the Inmate Thompson’s homeboy, showing up with a long gun, intent on liberating his buddy. Money would do me no good if I was lying in some scrub at the bottom of a cliff in a remote section of West Marin, my uniform pants around my ankles, a bullet through my head.

The first thing in my mind: This can’t be happening. Other useless thoughts flooded in. Why did I ever sign up to be a prison guard? Now I’ll never see Paris.

As the chief deputy continued talking to those who had gathered, months after the escape, the kidnapping scenes flickered through my head—the Inmate Thompson sliding into the prison transport van’s front seat, pushing the key into the ignition and grabbing the steering wheel, despite his waist chains and handcuffs. The old Chevy engine wheezed and backfired a plume of blue smoke as Thompson jerked the gearshift into reverse. In the front passenger seat, the gunman turned towards me, eyes narrowed. The barrel of the shotgun, cradled on his shoulder, rested against the perforated steel barrier that separated the front seat from the rear prisoner compartment, emitting a metallic rattle with each lurch of the van. In a moment we’d be on the road, our abductors driving us to God knows where.

No one was in sight, no sound from a car or radio. Even the birds were silent. The only noise was my heart thudding in my chest.

I’d wanted to squash my face against the steel screen and cry out, “Go ahead! Escape! I don’t care. But don’t hurt me . . . Don’t kill me!”

Ruff, the medic, sat motionless beside me, his hands folded over his beige uniform smock as if in prayer, his face pale as clotted cream.

Why hadn’t I turned down this medical run and just kept walking out the prison gate when my shift was over? I could’ve been home, safe in my bed.

Hare-brained schemes to attract attention clumped in my head. Yell at a pedestrian or passing car, or peel off my uniform shirt and wave it around. Naw, if anyone saw that, they’d just think I was some crazy Marin County babe having a hot flash. Plus, those moves would piss off the man with the gun.

Our abductors began arguing.

“Let’s tie ‘em up,” Hunt insisted.

I stopped breathing.

“Shit no.” Thompson steered the van to the deserted back side of the medical complex. “We gotta get out of here.”

Lucky for us, Hunt and Thompson were more interested in making it out of the state than in rape or murder. They left Ruff and me locked in the van’s prisoner compartment while they’d hot-footed it out of town.

Eventually, the long-planned European vacation with my boyfriend erased thoughts of San Quentin and the kidnapping. But memories of Hunt crouched in a dark corner of my mind like a child’s boogey man lurking under the bed, ready to claw into my consciousness. Still, the nightmare was over. Wasn’t it?

So why was the deputy warden taking about Hunt and Thompson now, months after the escape? I surveyed the room, my chest tight, my breathing shallow. The prison’s administrators sat stone-faced around the sprawling conference table, looking like they were waiting to hear the eulogy at someone’s funeral.

I was a lowly correctional officer, a prison guard. These silverbacks probably wouldn’t even have noticed me as they crossed the upper yard, wouldn’t have seen me admonishing a couple inmates who kept stepping over the out-of-bounds line near the canteen. So why was I sitting at a table with all the “suits”—the top brass?

At least it was warm in the conference room. The cruel March wind that crested over East Block housing kicked up bits of rotting bag lunches and torn clothing on the upper yard. Icy gusts battered me, no matter how many layers I wore under my uniform. I was almost glad to be here, near a heater.

“Hunt and Thompson were apprehended after a string of robberies in Washington State. They were returned to Marin County jail a couple days ago.” The chief cleared his throat. “A snitch at the jail told a deputy that Hunt was offering fifteen hundred dollars to have you eliminated.”

I pulled my Tuffy jacket closer, suddenly shuddering, despite the steam heater blasting in a corner of the room.

“Hunt must figure that if you’re out of the picture, the medic won’t testify against him.” The chief watched me, his eyes boring into my skull. “The DA would drop the case.”

The room was silent except for the periodic belching of the heater. I felt the administrators’ eyes on me. Waiting.

“I’ll testify.” My voice came out in a pathetic squeak, like a cornered mouse.

The chief nodded. “We’ll provide a house on grounds for your safety. And of course you’ll be assigned to a non-contact position—a tower job. It will be a couple weeks before maintenance finishes with a house in the valley.”

Ordinarily, this would’ve been good news. Getting staff housing with low rent and walking distance to work was highly coveted—most of the homes were reserved for the “suits” and higher-ups like lieutenants and the custody captains.

“This is confidential. Only staff who need to know about it are aware of the contract on your life,” the chief said at the end of the meeting.

Oh boy, secret shit. I couldn’t reveal the real reason why I was getting bargain on-grounds housing and a laid-back job assignment. But I did tell my parents—to prepare them in case I was killed. And I told my live-in boyfriend, so he could ditch this woman with a crazy career that might get him shot too. Instead, he stayed.

Trouble was, I’d have to lie to my work buddies—pretend it was pure blind luck that I’d gotten these goodies. I couldn’t mention the death threat, the contract.

While waiting for the house to be ready, I was shuttled off to CDC headquarters in Sacramento for safekeeping. Back at San Quentin, the rumor mill was in high gear. I’d been having sex with an inmate and had been arrested. How else to explain my disappearance?

Once I returned, I moved on-grounds and was assigned to a tower overlooking the waterfront warehouses, a place where nothing much ever happened, where my biggest worry was staying awake for eight boring hours. Soon the gossip changed. The new explanation for my supposed good fortune was that I was sleeping with one of the suits instead of an inmate.

No place felt safe except when I was in that tower, a Smith and Wesson strapped to my hip, a rifle leaning in a rack beside me. On-grounds housing wasn’t a real refuge—a six-foot chain-link fence was the only barrier between me and anyone wanting to earn fifteen hundred bucks. On the outside, I was on edge, waiting for a contract killer to leap from behind a trash can or whip out his Glock in the middle of Petrini’s Gourmet Grocery while I ducked for cover behind a display case of Belgian chocolates.

My mouth broke out in sores; I had insomnia and night terrors—waking up screaming, a hooded figure leaning over me, his gun glinting in the moonlight.

Turned out there were more steps I needed to take before going straight to court to testify against Hunt. First, there was a lineup. This wasn’t like those TV police dramas I’d watched as a kid—the ones where the witness to a crime would stand behind one-way glass, a sympathetic cop laying his hand on her shoulder as she gazed at the men lined up in a row in front of a height chart. “Take your time, ma’am,” the cop would say.

Instead, I was in a large auditorium in the Marin County Civic Center, fluorescent lights flickering overhead, chairs scattered haphazardly across the pocked linoleum floor. Ruff, the medic, and I were seated on opposite sides of the room. “So you can’t influence each other,” the DA said.

Seven jail inmates shuffled in, no cuffs or shackles, and lined up in the front of the auditorium about thirty feet away. I’d been mere inches from Hunt during the abduction and would never forget his acne-scarred face or ice-green eyes—as cold as a Dakota winter road. But I couldn’t see these details from where I was seated.

I guess I just accepted that this was how lineups worked in real life. I didn’t think to question the DA, to ask to move closer.

“Take a good look,” the DA said. “Oh, and the Afro wig was recovered.”

I’d almost forgotten Hunt’s absurd disguise. If he hadn’t been pointing a shotgun at me, I might’ve laughed at his Man-Tan smeared face topped by a cheap Afro wig. Like I’d mistake a biker-type white boy for a black man.

“You can have them put it on,” the DA said.

One prisoner twisted the wig so it sat sideways on his head; another pulled it low to cover his eyebrows. This was no help.

Leaning forward in the rickety folding chair, I examined each prisoner, straining to see each face clearly. Shivering, I folded my arms across my chest. I recalled failing a high school math test because I’d gotten confused; how stupid I’d felt.

I wanted to cry.

Finally, I narrowed it down to two possibilities. Everyone else was too tall or their build was wrong.

There. That man in the middle. It had to be Hunt. I felt it in my gut. But, did I trust my instinct?

Turned out the medic and I identified different people. The DA faced me. “How sure are you of your identification?”

I hesitated. I could’ve been one hundred percent sure if I’d been closer, but by then the inmates had all left the room. I should’ve asked for a do-over, requested to see the men up close. I should’ve lied. Instead I said. “Seventy, maybe eighty percent.”

The DA shook his head. “That’s not enough. We won’t prosecute.” I wanted to scream, maybe grab the DA by his starched Van Heusen shirt collar and demand he bring Hunt to trial, to give me a chance at a better look.

But I didn’t.

Instead, I just turned and walked out, pissed at myself that I’d let Hunt get away with nearly killing me—twice.

Christine Holmstrom’s work has been published in Bernie Siegel’s book, Faith, Hope, and Healing. Several of her essays and nonfiction stories have been published or are forthcoming in Gulf Stream, The Penmen Review, Jet Fuel Review, Switchback, Stonecoast Review, Summerset Review, Two Cities Review, and others.

This special issue features a 10-year retrospective from a couple of former editors-in-chief along with a letter from our founder. Jelly Bucket continues to showcase exceptional writing in genre categories of creative nonfiction, fiction, poetry, and art. The edition also highlights the work of poet Jeffrey Alfier. 160 pages.

Libby Horton

How to Call Your Father

Step One. Checklist.

Are you in an optimistic mood? If not, your atypical Buddhist father will suss this out. It would not be out of character for him to call for emergency services. If your mood does not pass muster, do not pass go.

How patient are you feeling? If you’ve recently yelled at your 3-year-old for refusing to wear pants, put the phone down and try tomorrow.

Are you feeling at all snarky? If the answer is yes, back away and open your laptop for some bad reality TV instead. People on those shows are a much better outlet than an over-pronating, retired nuclear physicist. After all, you are not a terrible daughter. Just an uncommunicative one.

Step Two. Prepare.

An adult beverage is required. The size of the glass should be proportional to the amount of time it has been since you last called. Choose an oversized goblet and fill it with rye whiskey plus a cherry or two (a poor woman’s Manhattan, you call this).

Step Three. Dial.

Note, with a twinge of remorse, that your father’s number has not made it onto your auto-populated list of favorites. (According to Google, the people you love most are your husband, your sister, and the pediatrician. This is an accurate estimation.)

Step 4. Hope.

Listen to the dial tones. Part of you hopes to leave a message. The rest of you hopes to hear his voice. Cross your fingers for both possible outcomes simultaneously. You are, after all, a deep and complicated woman.

Step 5. Contact.

Hear him pick up the phone and exclaim your name as if it has been a hundred years since he last heard your voice and you are the Buddha. Life is suffering, except when his wayward daughter calls. Next is the inevitable, “It’s been a while!” His tone is noticeably upbeat. Uncharacteristically upbeat. You suspect that your sister has warned him about guilt trips. Try to confirm this later.

Step 6. Caution.

Keep your voice optimistic at all times. If he senses a hint of familiar depression, he will try to talk you out of it. He will tell you how fortunate you are—a stay-at-home mom of two mostly healthy children with plenty of bonbons to eat, but all of this you already know. Logic-ing someone out of their mood is not actually a thing, but you have not convinced him of this. Or you have, and then he has promptly forgotten every time. He is in his 80s after all.

Step 7. Update.

“How are you?” he blurts out, before you have the chance to ask him the same question. Kick yourself for being slow on the draw. Then, give him the scoop on his grandchildren. Keep it brief and do not bring up anything that might cause him to worry. When you accidentally mention their recent bout of hand, foot, and mouth disease, take a swig of grain alcohol. Then, downplay the medical debacle with a cheery “They’ll be fine!” before he can utter the word prognosis.

Step 8. More Caution.

Again, do not mention anything that you are actually apprehensive about. Like the 75% chance your son will need eye surgery for his exotropia, because his eyes don’t track properly, and he could lose his binocular vision. Or how your husband’s travel schedule and not having the third baby you had envisioned has made your connection tenuous. Or how the ice maker’s sporadic crackings and rumblings turn you into a paranoid wreck every night. Avoid setting off his subconscious anxiety at all costs, because the sound of unparalleled concern in his voice is not something you want to have to shrug off, even if you are feeling optimistic and patient and not snarky.

Step 9. Retreat.

Pivot to an amusing anecdote of the toddler or canine variety. Like how your son peed in your husband’s cowboy boot and then went looking for your shoes. Or how the dog has been making herself sick all summer eating rotten crab apples in the backyard. Segue the dog tidbit into a question about Dad’s own rascally mutt Georgie. Then sit back for a description of the little hellhound’s recent kleptomania and destruction. He has probably felled the brick-weighted kitchen trash can, chewed up a library book, and defecated on freshly shampooed carpet, all within the last week.

Step 10. Share.

Talk about your own life. First, you are definitely busy. Try to remember exactly what you have been busy doing and latch onto your sweat-and-chalk-ridden gym obsession. Recount your recent deadlift personal record in impressive detail. 310 pounds is a big number. When he asks, “How high?” make a mental note to send him a video of a deadlift.

Move on by bringing up your garden, the new berry patch you just put in, and your efforts to acidify its soil. Also, neighborhood raccoons may have selected said berry patch as their latrine.

Step 11. Inquire.

Ask your father what he has been up to. As he catalogs the human interactions at his science museum docent gig, remind yourself that this is not the time for Google searches like “quiet time ideas for preschoolers.” If you breach this rule, you will stop hearing anything that he says and, after ten minutes, it will become clear to him that your mind is elsewhere. The disappointment in your father’s voice will be a dagger in your heart.

Step 12. Connect.

Fish a cherry out of your drink and settle into the couch as he tells you what he’s been reading. Something about geology, the nature of time, or particle physics. Again, avoid your laptop. You will have plenty of time to decide what show to binge on after you hang up. Listen as Dad tells you that plate tectonics will stop when the four radioactive isotopes responsible for heating the earth’s core run out, and after that it will only take 65 million years for the erosion of all land. Together you marvel at this amount of time, which is brief geologically, but incomprehensible to a life form that lives only 100 years, as far as order of magnitudes. Ask questions to demonstrate that you are both a) genuinely interested and b) still intelligent. You were, at one point, a PhD scientist after all. Dad reminds you that you have your PhD forever and no one can take it away from you. Resist the urge to say that sometimes you’d rather have a sturdy door stop it would be more functional.

Finally, lose touch with your inner monologue. Recount the story of a grad school cohort who became a theist after he decided that random mutations could not possibly account for the creation of the eye organ. Shake your head and commiserate about how your species is so bad at conceptualizing the amount of time it has taken for life to evolve on Earth. Realize that you do have knowledge and questions and opinions buried deep under the pro tips about stain removal and potty training and meal planning. Relish how interested your father is in thoughts that you don’t take time to contemplate, thoughts you can only share with him. Realize again, for the millionth time, that you are his daughter, that he raised you to think deeply and have your voice heard. Blink back a tear when he tells you how proud he is of you. Say “I love you,” a tradition your little sister started that you will be forever grateful for. Emotions come harder than science in your family. Say goodbye, reminded that the first man who ever loved you still does, from a thousand miles away.

Libby Horton is a lifelong writer and a recovering PhD chemist. She attends ongoing personal essay workshops at the Boulder Writing Studio where she is developing a collection of linked essays about the intersection of science, mental health, and relationships. When she is not wearing her writer hat, she is an avid downhill skier, an adequate gardener, and the steadfast mother of two small humans.

Purchase a Copy

Find a retail location here.

To order online, visit our store. Back issues are also available.

Current Issue – $12.00 per copy (additional copies $10 each)

Pre-Order Next Issue — $12 per copy (additional copies $10 each)

2-year Subscription — $20 (starts with next year’s issue)

Any Back Issue — $7 per copy

To order by mail, please fill out our order/ subscription form, found here.