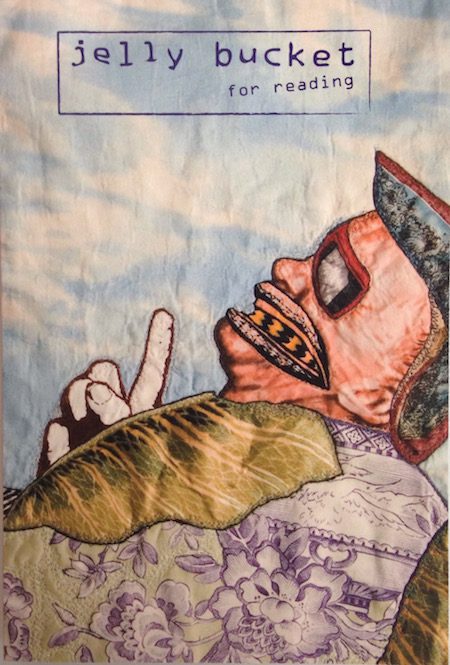

Featuring work by Angel M Baker, Richard Garcia, Chris Offutt, Henry Presente, Charles Rafferty, Tea Topuria, and many more, with cover art by China Marks. 190 pages.

Selections: Fiction

Issue #2: Fiction

Chris Offutt

Ghosts in the Attic

When I was six years old, my parents showed me a photograph of the new home we were moving to. I immediately proclaimed it to be a haunted house. My parents considered this evidence of my imagination, vast even for a child, and took possession of a large house on an isolated hill in eastern Kentucky, surrounded by the Daniel Boone National Forest. A dirt road led up the hill from the blacktop below.

The front of the house had four windows, two on the first floor and two on the second floor. Decorative shutters made of painted wood flanked the upstairs windows. The front door had a small, covered porch. Above its flat roof was another set of matching shutters. These, however, were shut, as if blocking an unseen window. Throughout my childhood, I believed those shutters concealed a secret entrance.

The house had three bedrooms—one for my parents, one for my sisters, and one for my brother and me. Our bedroom had a large closet, more of a small room actually, and inside was another door that opened to a narrow stairwell leading to the unfinished attic. The closed shutters were on the other side of the closet wall. I became certain that ghosts lived in the attic, entering and departing the house through the closed shutters. The closet provided them access to our room. My brother’s bed was against the far wall, but mine was beside the closet door. Each night I created a barrier of pillows to protect me from the ghosts. I kept rocks in my bed to defend myself in case they attacked. I slept at the far edge of the bed with my back turned to the door, my arms and legs tucked close. In this way I went to sleep in fear every night.

I did not have the kind of family that talked about personal concerns, and no one knew about any of this, not even my brother. Within a few years, prior to puberty, I developed the habit of sleepwalking, leaving the room to awaken elsewhere, occasionally outside. I often awoke from nightmares, sweating and scared, unable to recall what had transpired, knowing only that the ghosts had entered my room from the closet. I lay in bed rigid and tense, listening intently for evidence that a ghost still waited to ambush me as soon as I closed my eyes.

When I was twelve, my father quit his job outside of the house and began working from home. To accommodate this, he took my sisters’ small bedroom and they moved into my bedroom. My brother and I were relocated upstairs—the attic newly refinished but still containing evil ghosts. The space was long and narrow with a ceiling that slanted to low walls, which held two doors made of planks that opened to the eaves. I understood that the ghosts lived in there now, behind these flimsy doors, pushed into new quarters like my siblings and me.

To access my new bedroom, I was required to enter the dread closet through the creaky door and climb the dim steps to the completely dark room above. Worst of all, the only light switch was on the wall at the top of the steps. This presented a dilemma: did I sneak up the steps so as not to alert them, or make a mad dash and hope that my speed was greater than theirs. Each option had its own risks and gains. Both were fraught with terror. The sneaky way gave the ghosts time to position themselves. Racing up the steps offered me the advantage of surprise, but made me more vulnerable if the ghosts heard me. I decided on running upstairs, mainly to get the task over with quickly. I didn’t think I had enough courage for the slow approach.

I doubt my parents knew the degree of fear with which I approached my bedroom. They certainly never asked, and as oldest child, I didn’t want anyone to know how afraid I was. My brother and I never had a flashlight, nor was there ever any talk of one. Flashlights were reserved exclusively for those times when the electricity went off.

My brother refused to enter the room alone. Each night, he waited in the dark closet, while I inhaled deeply, ran swiftly up the steps, hit the light switch with my open palm, and jerked my head in all directions to check for ghosts. They were always gone. My speed and agility had beaten them again. Occasionally I saw the flicker of their disappearance as they returned to their haven in the eaves. For the next five years, I ended each day in this fashion until leaving home at seventeen.

Since then I have believed that every place I lived in was haunted. The previous occupants had probably left due to the presence of ghosts, and since most were rentals, I figured that’s why no one wanted to own the house in the first place. I’d spend the first week in a new place lying awake at night, learning each sound–the refrigerator’s motor, air in the water pipes, the rattle of a window casing, the whistle of wind. Over the years, I developed a variety of methods to keep the ghosts at bay. The most crucial was closing the closet door before going to bed. If the bedroom opened to a bathroom, that door needed to be shut as well, after checking behind the shower curtain. Bureau drawers were closed tightly, curtains were drawn, and the bedroom door itself double-checked that it was latched. Any rug was smoothed out. Though I have lived in more than forty different apartments and houses, I never discovered any evidence of ghosts, which was proof that my precautions were effective. However, I have always felt slightly disappointed. Seeing a genuine ghost would grant credence to the intense fear of my childhood room.

I spent more time outside our house than in, wandering the woods that surrounded the house. A couple of footpaths went along the ridges to a distant neighbor’s house, and another ran off the hill to the creek. Each morning I followed a path through the woods to school, a shortcut from one part of the dirt road to the other. I particularly enjoyed the woods at night, the mournful call of whippoorwill and owl, cicadas droning in the distance, the wind in the high boughs. The dark woods offered a solace that I relied upon. Later, after leaving home, I was surprised to learn that most people are afraid of the woods at night, that the menacing woods are a staple of fairy tales and pop culture. My experience was the opposite. Many times I left the house at night wishing I could remain in the woods forever.

My parents still live in the house I grew up in. They converted my old room in the traditional way of an abandoned nest – first to a sewing room, then to a study when my mother took classes, and lastly to a storage for junk. My siblings and I seldom go home. When we do visit, we get a hotel room in town. I recently spoke to my sister on the phone, and casually asked if she was ever afraid of the attic. She immediately said she was afraid of the whole house. I couldn’t answer because I had no idea what to say. I still don’t. My brother once told me that when he climbed the steps to our old room as an adult, something cold always passed through his body. He believed that it was the ghost of his fear.

On my last trip home, I stood in the dark closet at the bottom of the dark steps. The bedroom above was utterly black. I listened intently for any sound from the ghosts. I inhaled deeply. I placed my hands on the door jamb and used it to catapult myself up the steps, knowing just where to place my feet to avoid each creak, and at the top of the stairs my open palm hit the light switch and I jerked my head both ways and knew I had defeated the ghosts. I made it. I was safe. I was forty-five years old and had successfully entered my room again.

The contents of my former bedroom were organized into tall stacks that included Christmas decorations from the fifties, clothes from the sixties, and high school yearbooks from the seventies. There were broken toys and games with missing pieces, boxes of junk, dishes, magazines, and old luggage. My parents grew up during the Depression and their childhood fear was deprivation, not ghosts. My father saved soap slivers to prevent waste, and my mother has thrown away very little since moving to this house. She once informed me that she didn’t want to inconvenience the garbage men.

The room was ten times smaller than I remembered, as if the world of my childhood had shrunk. I wandered among the maze of piled objects, touching this and that. I handled things that were significant enough to save, but that I now barely recalled. It was like being at a yard sale, going through the remains of another person’s life. I had become my own ghost.

I found a charcoal sketch of my brother that someone made when we were kids. I remembered when it was drawn. At the time I didn’t believe it looked like my brother, but I knew that in the future everyone would think so. I held the picture in both hands, stunned that a child would have thought that way, more surprised that the child was me. I stared at the picture for a long time. It did in fact resemble my brother. Oddly, the drawing looks more like him now than it did then.

I crossed the room and turned off the light and stood in the dark. I didn’t feel afraid. It was just the storage room of an old house in disrepair. My memory was all that haunted the space. The hinges creaked on the door at the foot of the steps. I recognized the sound as one I’d many times opening the door slowly so the ghosts wouldn’t hear.

I thought of a young boy running up the stairs, his heart pounding, his feet finding each dark step, his hand hitting the light switch. He was lonely and imaginative. His parents were gone. I moved quickly and hid in the eaves so he would not mistake me for a ghost. At the top of the steps he jerked his head in all directions as the light came on. The room was safe. The light dispelled the ghosts. He was breathing hard.

He glanced at the area where I was hiding, the small door set in the low wall of the eaves. I held my breath. The boy stared at the crack between the door and the frame. I watched him swallow, his throat pulsing from fear. He walked to his bed, turned on the reading lamp, and returned to the top of the steps. He was deliberately not looking toward the eaves where I hid.

He turned off the overhead light and ran to his bed and jumped in. I knew that he would sleep with his arms and legs tucked beneath the thin sheet, no part of his body hanging off the edge of the mattress as an enticement to the ghosts. He would sleep that way the rest of his life.

When he at last did drift into sleep, I quietly left the eaves, opening the low door carefully, so as not to disturb him. I walked to the top of the steps. The room was very dark, but I could see his darker shape humped in the middle of the bed. I eased down the steps, knowing each tread intimately, able to find the precise spot that would not squeak.

At the bottom of the steps I faced a dilemma. The closet door always creaked when it opened, the hinges rasping, the swollen wood sticking in the jamb. It would be impossible to leave without making noise and scaring the boy. I stood for a long time in the dark closet, debating the options. I could sneak back up the steps or I could simply open the door. Either way, the boy would wake up terrified from a bad dream. At the same time, I couldn’t remain trapped in the darkness myself. I had to depart without disturbing the child above. I stepped close to the wall, opened the shutters easily, and left the house for the safety of the woods at night.

Chris Offutt grew up in Haldeman, Kentucky. He is the author of Kentucky Straight, Out of the Woods, The Same River Twice, No Heroes, and The Good Brother. He has written screenplays for True Blood, Weeds, and Treme, and TV pilots for Fox, Lions Gate and CBS.